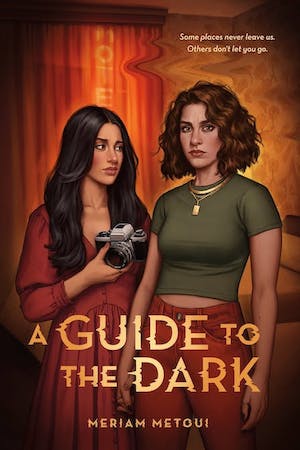

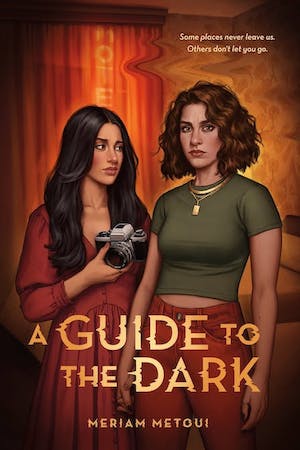

In Meriam Metoui’s debut young adult horror novel A Guide to the Dark, Mira and Layla are on the road trip of a lifetime. It’s spring break and they’re visiting colleges across the East Coast and Midwest. Both have their hearts set on schools in Chicago, but jump at the chance to spend some alone time together away from the pressures of their parents who immigrated from Tunisia and Egypt. Layla desperately wants to go to art school to study photography, but her parents strongly disapprove. They’d be even more disappointed if they ever figured out she’s queer and secretly in love with Mira. Mira, meanwhile, is out as bisexual to her family, but they have bigger issues to deal with. The year before, her younger brother drowned during a family vacation, and Mira blames herself. Both girls need a break, but all they find is a nightmare.

After a freak car accident on the way to Chicago, the girls suddenly find themselves stuck in a small town in the middle of nowhere. The only room available in the only local motel is the mysterious Room 9, in which, as they later learn, a suspicious number of people have died. There is something strange and quietly frightening about that room, but only Mira can sense it. Layla thinks everything is fine. But the ghost of Mira’s dead brother says otherwise.

Buy the Book

A Guide to the Dark

The girls seek help from two townies, Izzy the college student and front desk clerk, and Ellis, the son of the motel’s owner whose father died in that same room years before. Things go from bad to worse as the hauntings begin to stalk Mira around town. The only way to end things is to face her fears and confront her guilt.

In Western queer YA, we don’t often get stories where characters navigate their queerness and out-ness in relation to non-Western culture and traditions. Metoui dives into the baggage Layla and Mira’s immigrant Arab parents carry, particularly the anti-queer sentiments that were ingrained in them in the old country, which they’ve been unable or unwilling to shake in the new country.

It’s tempting to want to reduce everyone to good and evil, but there are as many complexities to how people grapple with queerness as there are ways of being queer. In the book, one character mentions how immigrants are often a snapshot of what their country was like when they left and how, even when they return, they can never really fit in. They’re forever caught in a time capsule, a diasporic experience in a liminal space. No matter what is changing in their homelands, Layla and Mira’s parents are trapped in the amber of the attitudes of their homelands when they first left them. Westernizing, even when it’s something as simple as inclusion and queer acceptance, can feel like losing what little you have left of your old life, no matter how much your Western-raised children might need you to change. It’s not that Layla and Mira’s parents are terrible people. They just have a more fraught journey to walk when it comes to processing their daughters being queer. Metoui handles this tightrope walk with nuance and respect.

On the technical side, the novel does some interesting things with narrative structure. Mira and Layla both get past tense first person POVs, while Room 9 or the entity within it gets a few of its own chapters in present tense third person POV. The photographs interspersed with the text are a creative and unexpected addition. However, they also somewhat hurt the narrative. Layla, our photographer, notes some strange warping around Mira in the photos but chalks it up to the lens being weird. However, the photos make it very obvious that the warping is only around Mira and that it’s getting progressively worse. Mira later admits she feels silly for not noticing it earlier, and yeah. It’s a pretty big thing to not notice, especially once they’re knee deep into ghosts and murder territory since the reader sees it right from the beginning. Also, the photos are in black and white, which unfortunately did not come out well in the final copy. The photos themselves are quite nice but the printing washed out the contrast so sometimes it’s hard to see clearly.

A Guide to the Dark is billed as “The Haunting of Hill House meets Nina LaCour.” Personally, I would’ve preferred more of the former and less of the latter. It’s not nearly as scary or emotionally distressing as it could be and is more “two teenagers pining over each other” than it probably needed to be. I’d give this to YA readers who need a stepping stone into horror or who don’t like being scared.

That said, I just appreciate this novel for existing. We’re in a diverse YA horror boom right now that is thrilling to experience. Queer YA horror is especially having a moment, and Meriam Metoui’s book is a solid addition to the pack. A Guide to the Dark offers identities and experiences readers rarely get to see in YA at all, much less in YA horror.

A Guide to the Dark is published by Henry Holt and Co.

Read an excerpt.

Alex Brown is a Hugo-nominated and Ignyte award-winning critic who writes about speculative fiction, librarianship, and Black history. Find them on twitter (@QueenOfRats), Instagram (@bookjockeyalex), and their blog (bookjockeyalex.com).